Positive Feedback Loops

Climate, capitalism, and our company

Of all the concepts I came across in high school biology, positive and negative feedback loops always stuck with me the most. One of the things that made them sticky is that I found the adjectives so unintuitive — ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ say really rather little about whether a particular loop is good or not.

For a negative feedback loop, consider body temperature. When you get cold, your body starts shivering to warm you up. When you’re too warm, your body starts sweating to evaporate heat. In both cases a system (your body) self-corrects to contain temperature within sustainable limits.

In contrast, a positive feedback loop is self-reinforcing. It’s a force that essentially spins a system out of control. Positive feedback loops are why games of Monopoly tend to end shortly after hotels start towering up.

Negative loops maintain the status quo. Positive loops perpetuate change. This post is about the latter — often scarier — kind of loop. It’s about how they are cropping up in nature, how they’re being triggered by our economic system, and how this system may in fact be underpinned by a loop of its own. Finally, I briefly consider how Verdn can tap into these loops to counteract other, more destructive ones.

Staying cool on a heating planet:

A few weeks ago, a heatwave saw temperatures in London rise to over 40 °C (104 °F) for the first time on record. Like most Londoners, I spent these evenings sweltering in an apartment without air conditioning (AC). The buildings here, if anything, are designed to keep heat in.

While the ostensible purpose of AC is to keep us cool, the irony is that it heats up the planet — both from the energy it requires and the atmospherically heat-trapping HFC gases that many AC units use. Worse yet, warmer temperatures create more demand for AC. It’s a system stuck in a positive feedback loop:

As the planet warms, humans will install more — and use more — AC to stay cool. Air conditioning units use huge amounts of electricity,1 most of which is carbon-intensive. Carbon-intensive electricity heats up the planet, necessitating even more AC, which requires ever-more electricity…

The scale of this problem is a lot larger than one might intuit. AC was estimated to use 10% of global electricity in 2016. Over the next few decades, demand will rise both as a result of warmer climates, and growing middle classes in developing nations. By one estimate, the energy used by AC is expected to triple by 2050, and by another it could account for as much as a 0.5 °C rise in global mean temperatures by 2100.

A song of ice and fire

Twelve thousand years ago, Earth emerged from its most recent ice age. Ever since, our planet has found itself in somewhat of a goldilocks zone of environmental conditions. The rise of modern civilisation was fully contingent on such a stable global environment.

One of the contributing conditions to this goldilocks zone was polar ice. The polar ice caps are a lot better at reflecting sunlight back into space than oceans and land. It’s called the ‘Albedo Effect’.

A little-known-fact is that we are still technically in the last ice age, because our polar ice caps persist year round. Humanity seems hell-bent on shedding this technicality as fast as it can.

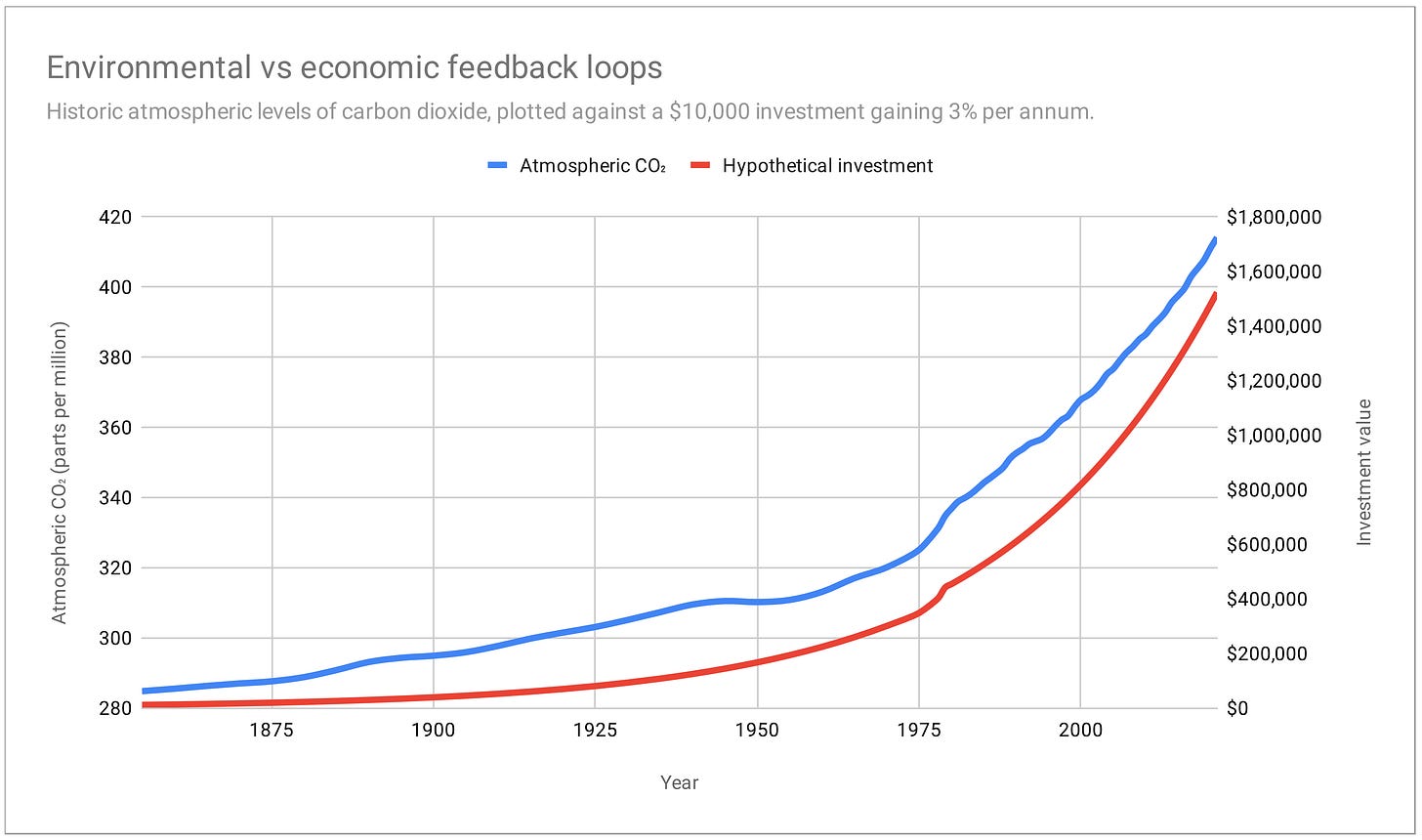

The density of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is measured in parts per million (ppm). Before the industrial revolution, atmospheric CO₂ was at 270 ppm. Now, less than three centuries after Spinning Jenny, it is over 410 ppm — a number not seen in at least one million years.

This would be bad enough by itself, but in fact it’s only getting worse — faster. Melting polar ice and increasing global temperatures are interlocked in a positive feedback loop:

As the planet warms, the world’s poles and ice caps melt. White ice reflects more sunlight into space than water and land do. As the surface area of ice decreases, the planet absorbs increasingly more solar radiation, which heats the planet more, which melts increasingly more ice…

While some positive feedback loops might theoretically spin out of control forever, there is a rising consensus that the planet may have certain emergency brakes. None of them are deemed comfortable, which is at least on-brand as far as the metaphor goes. One such brake might be the Gulf Stream, the North Atlantic current pumping warm water from the gulf of Mexico up to Northern Europe. It’s what makes the climate in Oslo different from Siberia — at least historically.

As the poles melt, trillions of tonnes of cold fresh water dilutes and upsets the Gulf Stream. The ocean current won’t stop overnight like in The Day After Tomorrow, but when it eventually slows down enough (and signs points to it being inevitable) the effects will be catastrophic. Part of Western Europe would be exposed to plunging temperatures in conditions mimicking a small ice age. Irony abound.

The Gulf Stream is currently at its weakest point in at least 1600 years.

The methane bomb

In large swaths of land in and around the Artic Circle (Canada, Russia) there is permafrost: ground considered to be frozen all-year-round. Global warming is thawing permafrost at completely unprecedented rates. This has scientists in panic mode because, as it turns out, there’s a lot of bad stuff locked away in that glacial soil.

One example of said bad stuff is disease. Scientists have been able to recover (and reanimate) smallpox and bubonic plague from permafrost. Mysterious cases of wildlife dying off have later proven to be anthrax seeping from age-old carcasses, finally able to decompose after hundreds or even thousands of years of stasis. Worst of all though, is the fact that embedded in the permafrost are billions of tonnes of methane, a greenhouse gas up to 100x more potent than carbon dioxide.

As the planet warms, permafrost melts to release gargantuan amounts of methane previously locked in the frozen ground. Methane is a greenhouse gas that traps heat in the atmosphere and warms the planet. The rising temperatures increase the rate of melting permafrost, which in turn increases the rate of released methane…

Triggering this “methane bomb” would quite comfortably take us past what’s considered a planetary tipping point. This single positive feedback loop would trigger others. The result would be runaway climate change in quite the literal sense, but there will be practically nowhere to run. Except for Elon, maybe?

Et tu, capitalism?

Capitalism is inextricably linked to the concept of growth. Most economic measures of growth are analysed with percentages: GDP per annum, revenue per month, you name it. Functions that grow consistently by some percentage value are exponential — their total value increase faster and faster.

In few cases is this illustrated more clearly than when looking at compounding interest, itself part of the very backbone of market economies. So powerful is this mechanism that Einstein is purported to have said that “compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world”.

It does seem like magic when you start running the numbers: $10,000 growing at 3% per year for 50 years is $45,000. Double the duration to 100 years and you don’t get twice the money, you get over four times the money: $200,000.

Read literally, Einstein’s quote implies that compound interest is a human invention worthy of standing alongside the Pyramids. That’s taking too much credit. Rather, it’s a case of humans unlocking and abusing the unfettered power of positive feedback loops. Capitalism, quite fundamentally, is the pegging of society to a mathematical axiom.

A principal investment yielding interest payments increases the total amount, which yields higher interest payments, which increases the total amount further still, ad infinitum…

The kicker here is that growth under capitalism has been in firm lockstep with rising energy demand, and energy has fundamentally correlated to carbon emissions in the same timeframe (renewables are only just starting to decouple this effect). Still, we choose growth: growth over sustainable development… Growth above all. Aligning society with this one positive feedback loop has thrown off the balance of nature and triggered a series of natural feedback loops in turn. These new forces, ever spiralling, may well come to challenge the very concept of the capitalist civilisation that instigated them.

An addendum: Spiralling positive change

Verdn’s mission has always been to make sustainability profitable. This is our company’s mission because a solution being profitable is a prerequisite for mass-adoption under capitalism.

In light of feedback loops and their power, this mission makes more sense than ever — but with a small twist. When we started on our journey two years ago, we wanted to prove that companies could use Verdn to donate a fraction of their revenue to sustainable causes, and in turn increase their bottom line.

We’ve since realised that the silver bullet is to prove that a larger positive impact has a larger effect on a company’s bottom line. This causal link, however slight, measured as a percentage, could trigger an unstoppable force:

By donating a portion of revenue to sustainability through Verdn, businesses attract and retain more customers. This makes the company more money which increases the level of sustainable donations. This, in turn, attracts and retains even more customers, which makes the business even more money…

There’s lots of work to do, but this is our North Star. We only have to get far enough for this more fundamental force of nature to take over.

Until next time.

Running an AC unit is comparable to continuously running a washing or drying machine