Solving Ocean Plastic

How to best tackle an 8-million-tonne-a-year problem

This is part two of an exploration into ocean plastic. Read part one here.

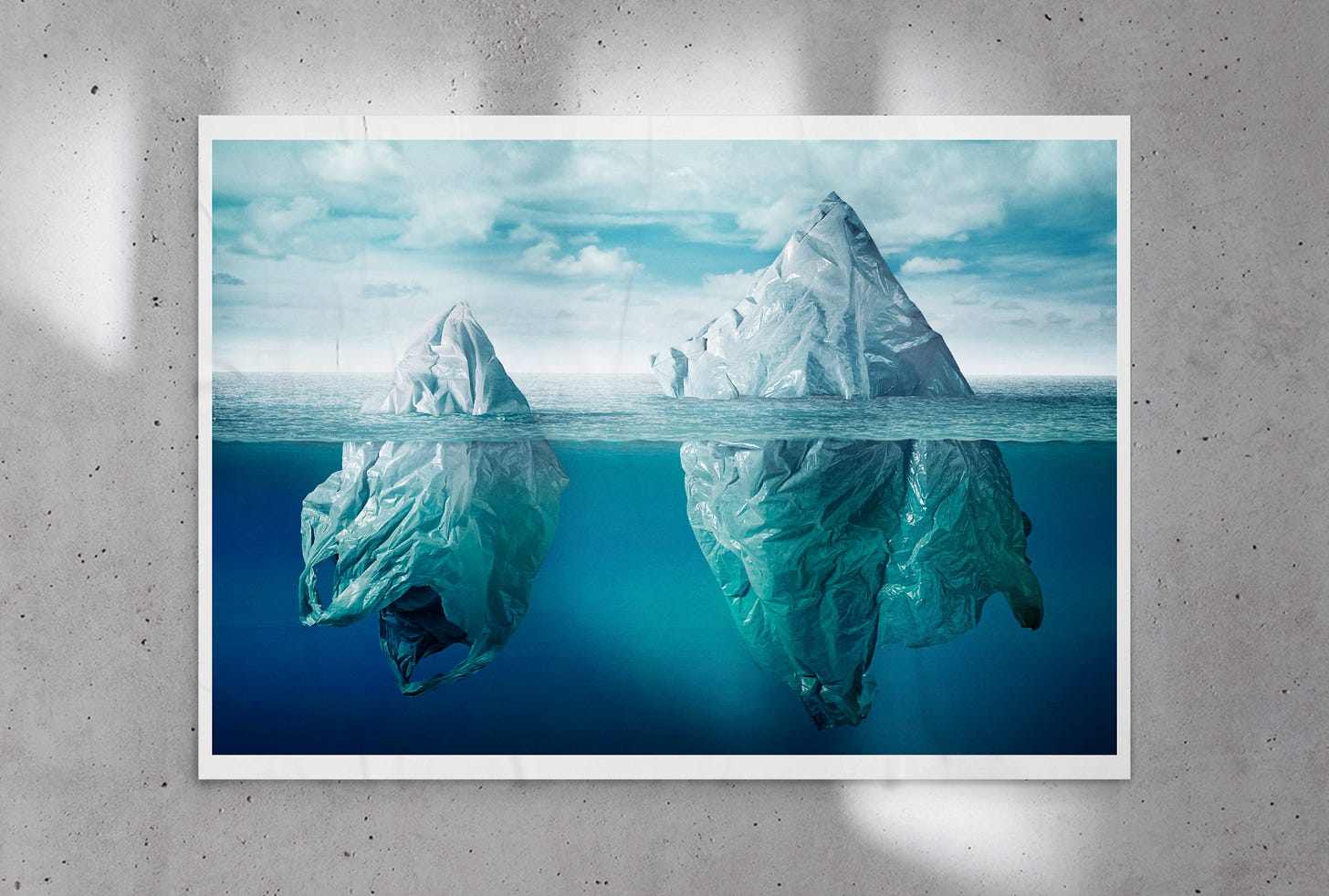

Ocean plastic is a stain on our collective consciousness, as well as a physical one on the blue marble we call home. In some regards, ocean plastic pollution has become the poster child for humankind’s planetary disregard.

It is estimated that over 8 million tonnes of plastic is added to our oceans every year. That’s 5 plastic bags of trash for every foot of coastline in the world, or a dumpster truck emptied into our seas every minute. Perhaps most repulsively of all, it is estimated that by 2050 ocean plastic will outweigh fish — all fish.

The global response has been all over the map, from international regulation banning single use plastic (potentially very good, in the long run), and the banning of plastic straws (which I have argued is ineffective), to private sector initiatives (everything from 4Ocean, to The Ocean Cleanup Project) trying to physically clean up the oceans.

Yet if our goal is to maximise our impact on ocean health, there is much lower-hanging fruit. The main one is this: recovering plastic at source, just before it escapes to sea. This is the same kindergarten logic that says if you’re emptying a bath, you turn off the tap before pulling the plug. The tap in question is our 8-million-tonne-a-year problem. And, as it turns out, turning it off might not be as hard as it sounds.

A Tale of 10 Rivers, and Globalisation

The reason we have a chance against the deluge of ocean plastic is because its origins are centralised. Indeed, quite remarkably so. As much as one quarter of all ocean plastic — 2 million tonnes a year — originates from just 10 rivers. Eight of these are in South East Asia, the last two in Africa. These rivers aren’t close to each other by chance: the majority flow through the same cluster of emerging economies, most of which have severe regulatory shortcomings that enable and perpetuate the situation.

The 10 rivers responsible for 25% of all ocean plastic

This is not happening in a vacuum. The regulatory issues of these countries have not only been known for decades, but have been purposefully exploited by the West in its quest for ever-cheaper consumption, fuelled by globalisation. Indeed, the West has grown utterly dependent on outsourced manufacturing to these parts of the world, where labour is cheap, conditions are poor, and the environment is ignored. These rivers flow through the same countries where all your Stuff™ is made.

Furthermore, the West engages in the same form of regulatory arbitrage with regards to waste itself. Half of all collected waste intended for recycling is traded internationally. That’s as much as 16 million tonnes — twice as much as the annual addition of plastic to our oceans. It’s traded because it’s cheaper. A lot cheaper: for San Fransisco recycling firm Recology, shipping waste to Asia saves 90% compared to domestic processing.

Just like the gyres of plastic in the great pacific garbage patch, a fleet of ships with literal garbage as cargo circulate the pacific every day.

The result is a sordid scenario. Not only are underprivileged workers labouring to make the innumerable things we consume in the West, but once we are done with them — like an older, careless sibling — we hand them back, broken, to be disassembled, destroyed, or simply thrown away. A lot ends up in rivers. A lot a lot.

Stemming the tide

Yet in all of this lies a huge opportunity. Not only do these 10 rivers make it possible to organise cost-effective plastic cleanup operations, but with the right business model, we could simultaneously provide high wages to hard-working, disadvantaged locals. The very same locals who have been shortchanged by globalisation, with no realistic capacity to caretake the environment given their current socio-economic conditions.

Enter Empower, Verdn’s plastic cleanup partner.

An Empower ocean plastic cleanup on the coast of Mumbai, India

Inspired by the Norwegian bottle deposit system (one of the most effective recycling schemes in the world), Empower is establishing a global plastic waste ecosystem that gives plastic a fixed monetary value.

In every country they enter, Empower establishes collection points together with local partners (NGOs or charities), providing financial rewards to all those who deposit waste. All plastic is digitally registered upon collection, allowing Empower to trace the recovered plastic back up the supply chain, while helping them keep tabs on how it’s reused. They’ve already organised cleanups in more than 15 countries, including those that see the Niger, Mekong and Ganges rivers flow through them (all members of the 10 usual suspects).

This is how Empower’s and Verdn’s business models work in tandem to create value and change:

A consumer buys an ‘impact product’ that pledges ocean plastic cleanup from a brand using Verdn’s software.

Verdn sends the impact fee to Empower, which allows them to guarantee a financial reward for deposited plastic at their collection sites in Africa and Asia.

The local waste pickers earn a stable, high-paying (and indeed sometimes life-changing) wage from recovering plastic.

Empower sends tracking data back to Verdn, which allows us to inform each consumer when and where plastic was collected on their behalf.

This model has the potential to enable a massive redistribution of wealth from the West back to the world’s poor, and we do it by fully monetising the rising trend of conscious consumerism and directing the funds to where it matters most.

And it matters more now than ever. Due to country-wide lockdowns, waste pickers across the world have been unable to do their job, and they’ve lost their incomes as a result. In response, Empower has set up a Waste Picker Aid Fund, essentially a micro-loan service, that ensures some financial continuity for locals in exchange for future plastic deposits. If you have the means to donate, you can do so here.

Until next time.

I'm not reeeeealy Bono (to all my fans out there) but I think my nick from the previous article is stuck with me forever

There is a lot of plastic out there or not nearly as much fish as I thought there were. Fish are weird, right? The article seems to suggest the latter though. We do use quite a bit of plastic...